Modern Western Buddhism functions remarkably like an avoidant attachment strategy dressed in spiritual robes. This isn't immediately obvious - the language is all about awareness, presence, and acceptance. But watch closely how these teachings typically get enacted: sitting alone on your cushion, maintaining emotional distance through "equanimity," pursuing individual enlightenment while treating intimate relationships as distractions. We've created a spiritual technology perfectly appealing to individuals with avoidant attachment.

This isn't a critique of Buddhism itself, but rather of how Western culture has shaped Buddhist teachings through the lens of its own intimacy disorder. As David McMahan explores in The Making of Buddhist Modernism, what we think of as Buddhism in the West is largely a modern creation, filtered through Protestant Christianity, scientific rationalism, and Romantic idealism. But there's another influence at work: our cultural pattern of avoiding intimacy.

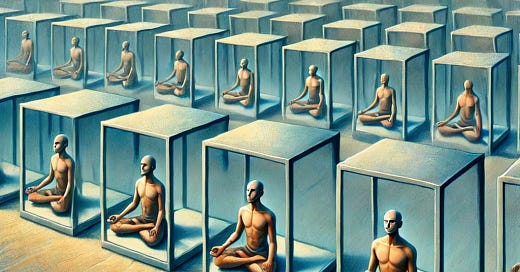

The Comfortable Distance of Western Buddhism

Consider how Buddhist teachings about non-attachment typically get presented in the West. In practice, these teachings frequently translate into cultivating emotional distance and self-containment. We're taught to observe our emotions rather than enter into intimate relationship with them (or, God forbid, embody them with passion). Meditation becomes a way to transcend rather than deeply know ourselves. Even mindfulness, stripped of its traditional context, becomes primarily a technology for maintaining comfortable distance from our experience. Consider Jon Kabat-Zinn's now classic definition of mindfulness, oft quoted in training seminars the world over: "Mindfulness means paying attention in a particular way: on purpose, in the present moment, and non-judgmentally." This emphasis on being "non-judgmental" trains us to disengage from our evaluative responses rather than developing a more intimate relationship with them—reinforcing the pattern of avoidance under the guise of spiritual practice.

This transformation is particularly visible in how modern Buddhism approaches difficult emotions. Rather than seeing them as manifestations of our embodied intelligence and an invitation to deeper intimacy with our experience, they become problems to be managed through observation. The language of "letting go" often masks a pattern of emotional avoidance. We're taught to watch our feelings arise and pass away, as if getting too close to them would somehow compromise our spiritual development.

What I've Seen in Practice Centers

After spending nearly eight years living in various Buddhist practice centers, I've observed a pattern that's difficult to ignore: Western Buddhism seems to attract people with predominantly avoidant attachment styles. To be clear: I'm describing my own patterns as much as others'. I've lived this avoidant dharma from the inside out. These are often individuals who are, consciously or unconsciously, retreating from the messiness of intimate relationships and the demands of everyday social life.

The pattern becomes especially visible when dedicated practitioners fall in love. Many struggle profoundly, their lives turning upside down as they confront the intimate terrain they've been skillfully avoiding through practice. Having developed sophisticated techniques for maintaining emotional distance, they find themselves ill-equipped for the raw vulnerability that real relationship demands.

While this dynamic exists in many spiritual communities, I've witnessed it most clearly in Western Buddhist contexts. These spaces often become refuges for those struggling with insecure attachment, people seeking alternatives to mainstream society's relationship patterns but not necessarily finding healthier ones. Instead, they often discover spiritual justifications for maintaining their emotional distance.

The Mindfulness Industrial Complex

The mindfulness industrial complex takes this tendency to its logical conclusion. Difficult emotions become inefficiencies to be smoothed out. Relationship challenges become opportunities to practice non-attachment and 'non-violent' communication instead of opportunities to break through to deeper connection. Even the profoundly intimate experience of breathing gets transformed into a technique for emotional regulation. The revolutionary potential of Buddhist practice - its ability to radically transform our fundamental relationship with life - gets reduced to a set of stress management techniques.

What's lost in this interpretation is the rich tradition of devotion, community, and relationship with sacred world that has characterized Buddhist practice throughout history. The historical Buddha didn't lead or teach a life of isolation - he created a sangha, a community of practice, and said that friendship is the 'whole of the path'. Without these elements, we're left with a hollow shell, meditation techniques without the transformative context they were designed for.

The Cost of Spiritual Bypassing

The costs of this spiritual bypassing are significant. People can spend years or decades practicing meditation while their fundamental patterns of insecure attachment and avoidance remain unchanged or even strengthened. The language of non-attachment provides sophisticated justification for avoiding actual contact with experience. "Going deeper" often means moving further away from the messy reality of embodied human life.

Corporate mindfulness programs, meditation apps, and secular Buddhism all tend to emphasize aspects of practice that maintain comfortable distance from the intensity of experience. The radical potential of Buddhist practice gets domesticated into something safe, controlled, and fundamentally avoidant. Slavoj Žižek once argued that Buddhism "functions as the perfect ideological supplement" to Western late capitalist society, enabling individuals to participate fully in market activities while maintaining an appearance of mental tranquility, thus accommodating the existing system rather than challenging it.

Toward a Non-Avoidant Buddhism

What would a non-avoidant Buddhism look like? Perhaps it would recognize that freedom comes through deep participation with all dimensions of life rather than withdrawal. It might value emotional depth and expression alongside spacious clarity, understanding non-attachment as a basis for connection rather than as a way to defend against it. Perhaps it would orient towards developing secure attachment with reality.

This isn't about rejecting Buddhist teachings but about recognizing how our culture has shaped our interpretation of them. By becoming aware of these patterns, we can engage with Buddhist wisdom in ways that heal rather than reinforce our cultural blindspots. Then can we begin to discover what Buddhism might offer beyond its current maladaptive form - perhaps something more alive, more intimate, and ultimately more transformative than our current stress-reduction paradigm affords.

Work with me: I offer one-on-one guidance helping people develop secure attachment with reality through deep unfoldment work. If this resonates, explore working together

You make some keen observations about Western Buddhist practice as well as mainstream mindfulness culture. I've noticed many of the same tendencies, including in myself at times.... but one thing that's nagging at me--don't you think some of the problem you're describing is rooted in the suttas? Yes, Western culture has translated and co-opted Buddhism in a way that reinforces our avoidant patterns, but from what I've read of the Pali suttas (in translation) there also seems to be a tendency toward avoiding "negative" emotions, attachment to worldly concerns, and of course, the emphasis on monasticism and celibacy... even the descriptions of the goal in terms of becoming a "non-returner" or arhat seem to emphasize transcendence of this world, and certainly romantic relationships. Personally I've gravitated toward Vajrayana and feel some ambivalence toward the suttas for that reason.

I really related to this article and appreciate your description and insights. I spent 17 years in a traditional Buddhist sangha led by a western teacher. So many unpleasant emotions like jealousy and competitiveness would come up over and over just trying to get along or pull together as a group for a special event or ritual and I always felt like a failure for not being able to let go or to even have feelings in the first place. It was very confusing. I finally left my teacher and community and found my way into social tango dancing. It’s like being in a sangha in many ways, however this time there is a lot of physical contact, and emotional expression actually helps you in your dance. Fortunately I also feel like some of the skills I developed in my Buddhist community like concentration and compassion have really helped out my dance practice. It’s so important to take the big picture view like you are doing here, and I really appreciate what you have written. Sometimes I wonder if we just have to go through what we went through….