The Upper Middle Path and Tech Bro Buddhism

Analyzing how progressive politics and Silicon Valley thinking have domesticated the revolutionary potential of Buddhist practice

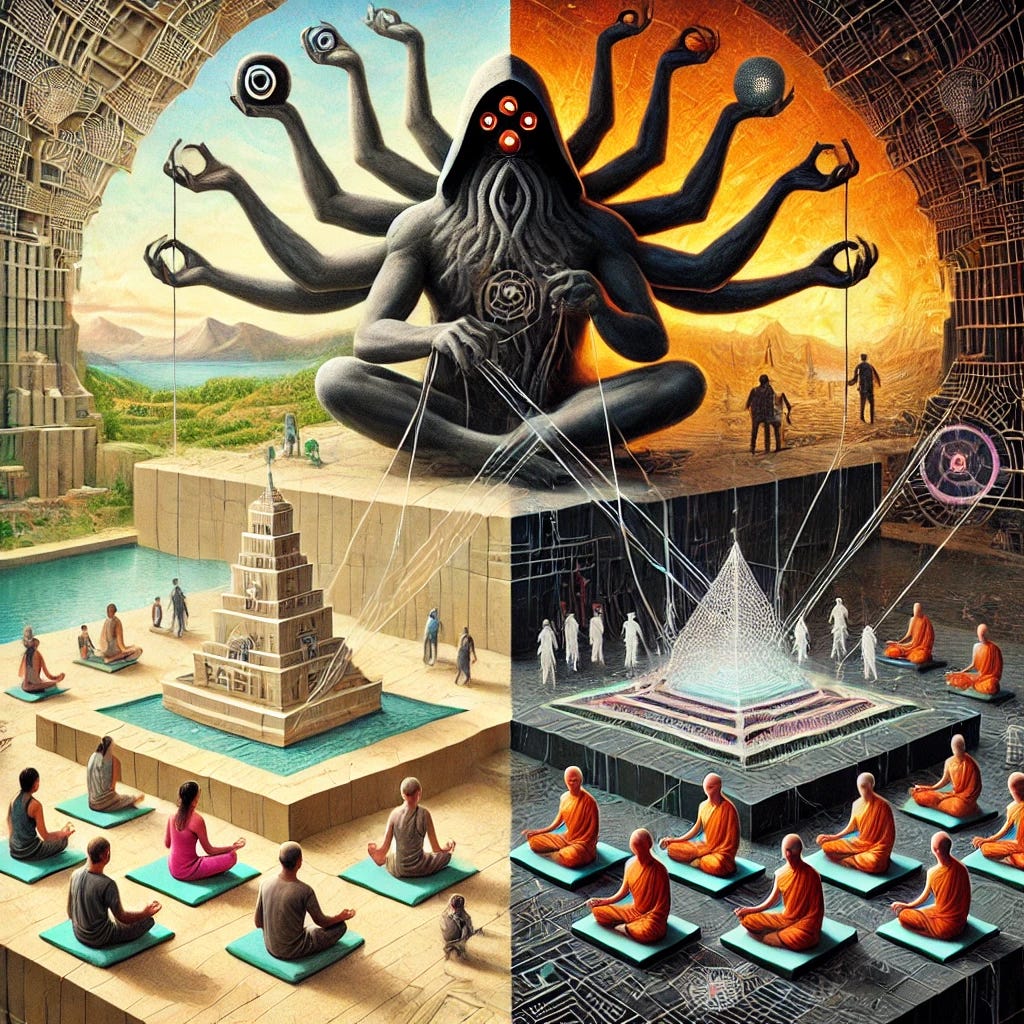

Western Buddhism has evolved into two distinct cultural expressions that, while appearing quite different on the surface, reveal complementary limitations. On one side stands Consensus Buddhism—accessible, psychologically-oriented, and deeply aligned with progressive politics. On the other stands Pragmatic Dharma—technical, results-focused, empirical, and deeply influenced by Silicon Valley's techno-libertarian worldview. While they seem to represent opposing approaches, both ultimately domesticate Buddhism's revolutionary potential in ways that reflect Western cultural biases.

This continues my series examining how Buddhism has been transformed through its encounter with Western culture. Having explored how Western Buddhism often functions as an avoidant attachment strategy and how secular materialism has unbundled Buddhist teachings, I now turn to these two dominant strains—not merely to describe them, but to examine how each, in its own way, adapts Buddhism in ways that often leave our fundamental cultural blindspots and confusions unchallenged.

The Great Divide: How Western Buddhism Split

The seeds of this division were planted in the 1960s and 70s when Buddhism first gained traction in the West. Young Americans and Europeans traveled to Asia, studied with various teachers, and returned to establish meditation centers and communities. Early Western Buddhist pioneers like Joseph Goldstein, Jack Kornfield, and Sharon Salzberg studied with traditional teachers but were already beginning to adapt these teachings for Western audiences.

By the early 2000s distinct streams had emerged. Mainstream institutional Buddhism evolved toward what David Chapman has termed "Consensus Buddhism"—a blend of various traditions with strong psychological integration, increasingly based in major meditation centers and represented in popular books and magazines. Simultaneously, a counter-movement emerged among practitioners seeking more intensive approaches and clearer markers of progress, eventually coalescing into what became known as "Pragmatic Dharma."

These two streams attracted different demographics and temperaments. Consensus Buddhism appealed broadly to educated professionals, particularly those in helping professions, with its accessible language and integration with therapy. Pragmatic Dharma drew technically-minded individuals—engineers, programmers, and rationalists—who sought clarity, systematization, and measurable results.

The institutional expressions likewise diverged. Consensus Buddhism flourished in established centers like Spirit Rock and Insight Meditation Society, supported by popular teachers with books published by major presses. Pragmatic Dharma lived primarily online—on forums like Dharma Overground, in podcasts like Buddhist Geeks, and through independent teachers operating outside traditional structures.

Consensus Buddhism: The Blue Church Dharma

Consensus Buddhism represents Buddhism processed through the filter of liberal progressive culture and Blue Church orthodoxy. Joseph Goldstein's "One Dharma" stands as its foundational text—a well-intentioned attempt to create an integrated approach that draws from various traditions while emphasizing accessibility and psychological integration. However, this ecumenical approach often results in a dharma that selectively incorporates elements that resonate with Western sensibilities while filtering out aspects that might more profoundly challenge our cultural assumptions.

The hallmarks of Consensus Buddhism reveal its particular biases:

An ecumenical approach that draws from multiple traditions but often dilutes their more demanding or culturally challenging elements

Strong subordination to Western psychological frameworks, sometimes reducing liberatory teachings to self-help techniques

An emphasis on gentleness and accessibility that, while valuable, can sacrifice depth for palatability

Reframing of meditation primarily as stress reduction and emotional healing rather than fundamental transformation

A secularizing tendency that maintains some traditional elements while removing anything that seriously challenges materialist assumptions

This movement has undeniably made meditation accessible to millions of Westerners who might otherwise never have encountered Buddhist practice. Centers like Spirit Rock and Insight Meditation Society have created spaces where people can learn meditation without requiring intensive commitment. Yet these centers also tend to attract predominantly white, affluent practitioners, creating spiritual environments that sometimes feel more like wellness retreats than transformative practice communities. My friends and I sometimes jokingly refer to such spaces as the 'upper middle path'.

Over time, Consensus Buddhism hasn't just aligned with progressive politics—it has become increasingly defined by it. What began as genuine connections between Buddhist principles and environmental or social concerns has evolved into something approaching political capture. The dharma increasingly functions as a spiritual complement to political identity rather than as a liberatory path that might transcend or challenge political frameworks altogether.

This political alignment intensified in recent years as practice communities explicitly adopted diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) frameworks. Communities began examining their predominantly white, upper-middle-class demographics, making efforts to diversify both sanghas and teaching bodies, and incorporating social justice language into dharma teachings.

When Consensus Buddhism Meets Political Ideology

The integration of Buddhist teachings with progressive political frameworks has created significant tensions. Perhaps the most fundamental contradiction lies in their approaches to suffering and agency. Traditional Buddhism emphasizes radical self-responsibility—the understanding that while external conditions matter, our relationship to those conditions ultimately determines our suffering. In contrast, contemporary progressive frameworks often encourage a victim mentality where one's suffering is primarily attributed to external systems of oppression, with personal agency downplayed or even dismissed.

This tension extends to other core elements. Buddhist practice centers on the deconstruction of identity, seeing attachment to fixed self-concepts as a primary source of suffering. Modern identity politics, however, typically strengthens identification with social categories, treating them as fundamental rather than constructed. The Buddha identified craving and ignorance as suffering's roots, while progressive analysis focuses heavily on oppressive systems as the primary causes of harm.

These aren't merely philosophical tensions—they manifest concretely in practice communities. I've witnessed teachers who once emphasized the liberatory potential of non-self now hesitating to challenge students' increasingly rigid identifications with various identity categories. The fear of appearing politically incorrect has sometimes limited the full expression of essential Buddhist teachings about the dangers of identity-clinging.

Some practice centers have struggled significantly with these contradictions. During 2020-2021, established Buddhist communities effectively suspended normal operations for months (even as pandemic suffering peaked) to address internal political and social justice concerns. Centers like Spirit Rock and San Francisco Zen Center redirected significant resources toward DEI initiatives and internal examinations rather than serving their broader communities during an unprecedented crisis. This pattern reflected a broader phenomenon documented in Ryan Grim's widely-discussed article "Elephant in the Zoom: Meltdowns Have Brought Progressive Advocacy Groups to a Standstill at a Critical Moment in World History" (The Intercept, June 2022), which detailed how many progressive organizations became functionally paralyzed by internal identity conflicts precisely when their services were most needed.

I've heard from friends with first-hand experience that at Spirit Rock, individuals are being positioned into teaching roles based significantly on identity characteristics rather than primarily on the depth of their realization or teaching skill. This approach directly contradicts traditional dharma transmission criteria based on wisdom attainment rather than demographic categories. Such decisions inevitably undermine the integrity of whatever lineage is being developed and diminish confidence in the quality of teaching available at these institutions.

Core Buddhist principles like the questioning of all views (dṛṣṭi) can become difficult to maintain when they conflict with strongly held political convictions. The result isn't necessarily Buddhism enriched by social awareness but sometimes Buddhism subordinated to political identity—a spiritual practice that may comfort rather than challenge practitioners' existing worldviews.

Pragmatic Dharma: The Tech Bro Buddhism

As Consensus Buddhism became increasingly mainstream and politically oriented, another approach developed among practitioners seeking more intensive methods and clearer markers of attainment. The "Pragmatic Dharma" movement emerged from the confluence of traditional meditation techniques, Western empiricism and pragmatism, and internet culture, eventually evolving into what might be called "Tech Bro Buddhism"—a strain particularly resonant with Silicon Valley values and approaches.

This movement began with teachers like Shinzen Young, who developed systematic approaches to meditation practice, and gained momentum with Daniel Ingram's controversial "Mastering the Core Teachings of the Buddha"—a book that demystified meditation while sometimes inflating the spiritual ambitions of analytically-minded practitioners. The movement found its digital home on forums like Dharma Overground and through projects like Buddhist Geeks, creating communities where awakening was discussed as a technical achievement rather than a mysterious transformation.

This approach is characterized by distinctive tendencies:

A strong emphasis on results, techniques, and systematic practice that sometimes treats awakening like an optimization problem

Focus on classical attainments divorced from their ethical and cultural contexts

Technical language and detailed "maps" that sometimes function as status markers within the community

An approach to awakening that can resemble achievement-hunting more than genuine spiritual transformation

Faith in technology and measurement as primary tools for evaluating practice

Skepticism toward traditional authority while sometimes unconsciously recreating guru dynamics in online forums

A willingness to experiment with ancient practices in ways that can be both innovative and potentially ungrounded

The appeal to technically-minded practitioners is clear. Pragmatic Dharma offers clarity about goals and methods, measurable markers of progress, and a community that values direct experience over received wisdom. It strips away cultural elements that might feel foreign to Westerners while attempting to retain the technical core of practice.

This approach has helped many practitioners achieve significant insights and states. By demystifying meditation and focusing on practical results, Pragmatic Dharma has made intensive practice accessible to individuals who might be alienated by more traditional or new-age presentations. However, it also often reflects the same values and limitations that characterize Silicon Valley culture—including an individualistic achievement orientation and a tendency to reduce complex human realities to technical problems.

The Shadow Side of Tech Bro Buddhism

Despite its strengths, Pragmatic Dharma carries significant shadows. The technical, achievement-oriented approach often attracts individuals unconsciously motivated by feelings of inadequacy or alienation from mainstream culture. Practice becomes a way to escape social disconnection or to achieve special status through spiritual attainment.

Having spent years in these communities (and I include myself in this critique), I've observed how this approach can create an atmosphere of subtle competition. Practitioners sometimes compare attainments, debate technical points of meditation theory, or claim superior understanding in ways that mirror the status-seeking behaviors in other fields. This intellectual focus often masks an emotional immaturity that can persist despite significant meditation experience.

The community tends to attract individuals (predominantly men) who find themselves alienated from mainstream culture and unconsciously seek refuge in spiritual practice. Enlightenment becomes a kind of MacGuffin—a compelling but elusive goal that promises to resolve emotional wounds, relational difficulties, and existential confusion. The pursuit of awakening fuels intense striving toward transcendence and technical mastery, often accompanied by an intellectual superiority disguised as performative humility.

I've participated in conversations where practitioners impressed each other with technical meditation jargon while looking down on "less serious" practitioners of Consensus Buddhism. There's often a striking gap between intellectual understanding and emotional intelligence, creating communities where technical knowledge outpaces relational capacity. The same person who can describe the subtle nuances between different jhānic states may struggle with basic emotional intelligence in relationships.

The Pragmatic Dharma community's relationship with traditional authority reveals another shadow. While healthy skepticism toward authority has value, this community often displays a reflexive distrust of traditional structures that suggests underlying unresolved issues with authority itself. There's a pervasive DIY attitude that cherry-picks techniques and teachings without fully understanding their context or the potential risks of "fucking with that which you don't understand."

This distrust often connects to deeper patterns of masculine wounding and confusion about legitimate authority. Rather than developing discernment about healthy versus unhealthy authority, there's often a blanket rejection of tradition and lineage—only to unconsciously project authority onto technical systems, maps, or charismatic figures who operate outside traditional structures. The authority doesn't disappear; it just gets redirected in ways that often escape conscious examination.

The Enlightenment Button Problem

One of the most concerning aspects of Tech Bro Buddhism is what I call the "enlightenment button problem." The intense desire to streamline the path—evident in the constant refinement of techniques and interest in technological interventions like Low Frequency Ultrasound—reveals a fundamental misunderstanding not just of awakening but of suffering itself.

The fantasy is understandable: what if we could simply press a button or use a device to instantly achieve the neurological state corresponding to enlightenment? But this technological approach doesn't just treat awakening as a brain state to be engineered—it fundamentally misconceives the role of suffering in human development.

Here's what's missed: suffering isn't wrong and to be eliminated. Suffering is meant to be understood. It serves as a crucial feedback mechanism that teaches us how to be in right relationship with ourselves, others, and the world. The Buddha didn't teach the elimination of suffering as an end in itself, but rather offered a path to understand suffering so deeply that we transform our relationship with it. The technological approach, by contrast, seeks to bypass this understanding and simply remove the subjective experience of suffering.

This reflects the deeper shadow of Tech Bro Buddhism. Rather than a path toward the opening of sacred world, it becomes a path of "fixing" reality so that it conforms to the mind's desire for comfort. Instead of transforming our relationship with what is, we try to engineer what is to match our preferences. The enlightenment button represents the apotheosis of this mindset.

The danger isn't merely theoretical. If such technologies actually succeeded in producing states of non-suffering or non-self without corresponding ethical development, they could create what we might call "enlightened monsters"—individuals who don't experience personal suffering even as they cause suffering for others, who lack the personal distress that might otherwise guide their behavior.

Consider how suffering works within the realm of ethics and relationships. When we act harmfully—when we lie, cheat, steal, or otherwise breach our relational bonds—we suffer, and that suffering informs us about how to refine our behavior. This feedback loop is essential to ethical development. If we simply eliminate this feedback mechanism through technology, we exit the very system designed to teach us how to live well.

Imagine the investment banker who uses technology to achieve "awakening" that frees him from anxiety and self-doubt, but continues to engage in predatory financial practices without experiencing the natural suffering that such harmful actions should generate. Or the tech CEO who experiences "non-self" yet builds addictive platforms that undermine social cohesion, never feeling the ethical discomfort that might otherwise lead to course correction.

This represents a profound misunderstanding of the dharma: the belief that freedom from suffering is primarily a subjective, individual state to be achieved rather than a relational way of being to be cultivated. Traditional paths intertwine ethical development with meditative attainment precisely because they understand that true liberation cannot be separated from how we relate to others and the world.

The technological approach, with its focus on individual states and experiences potentially divorced from ethics and compassion, risks creating precisely the sort of spiritual bypass that traditional paths were designed to prevent. By short-circuiting the very feedback mechanisms that guide human ethical and relational development, the enlightenment button would not lead to awakening but to a form of spiritual lobotomy—a state of personal comfort achieved at the expense of the wisdom that suffering is meant to cultivate.

What We Can Learn From Both Approaches

Despite these shadows, both strains of Western Buddhism offer valuable elements worth preserving.

Consensus Buddhism brings accessibility, gentleness, and psychological sophistication. Its integration with therapeutic approaches has helped many individuals heal emotional wounds that might otherwise obstruct deeper practice. Its emphasis on compassion and inclusivity creates entry points for diverse practitioners. The skillful translation of traditional concepts into accessible language has made Buddhist insights available to millions who would never enter a traditional monastery.

Pragmatic Dharma contributes empirical clarity, systematic practice, and honesty about goals. Its willingness to directly discuss awakening as an achievable aim rather than a distant ideal has empowered many practitioners to take their practice seriously. Its emphasis on direct verification rather than received wisdom aligns with the Buddha's own empirical approach. Its questioning of calcified traditions has helped distinguish essential elements from cultural accretions.

Beyond the False Dichotomy

The challenge now is to move beyond this false dichotomy—to integrate the strengths of both approaches while addressing their limitations. What might this integrated approach look like?

It would likely combine Consensus Buddhism's psychological sophistication and compassion with Pragmatic Dharma's clarity and intensity. It would honor traditional wisdom while engaging critically with it. It would value both individual transformation and social engagement, seeing them as complementary rather than opposing forces.

Most importantly, it would recognize that awakening isn't just about states and experiences but about a fundamental shift in one's relationship with life. Neither psychological well-being nor technical attainment alone constitutes the full promise of Buddhist practice. The dharma's true potential lies in how it deconstructs what obstructs sacred world, opens us to the living reality of this sacred dimension, and empowers us to find our right relationship within it. Through this process, we become capable of both protecting what is sacred and participating in the creation of new worlds aligned with deeper truths. The goal isn't just personal comfort or achievement but a radical reorientation that allows us to recognize, honor, and serve what is most real and valuable.

What's needed isn't another brand of Buddhism competing in the spiritual marketplace, but an opening of the radical heart of the dharma—one that challenges our materialist assumptions, our political identifications, our technological fantasies, and our spiritual consumerism simultaneously. Such an approach might preserve the revolutionary potential of Buddhist practice while making it genuinely accessible in contemporary Western contexts.

Conclusion

The division between Consensus Buddhism and Pragmatic Dharma reveals something important about Western culture itself—our tendency to separate heart and head, compassion and clarity, relationship and truth. Each strain represents a partial expression of the Buddhist path, emphasizing certain elements while neglecting others.

Consensus Buddhism shows us a well-intentioned but sometimes compromised attempt to make dharma accessible and relevant to contemporary concerns. It risks being captured by the very psychological and political frameworks it could transform. Pragmatic Dharma reveals a technically sophisticated but sometimes emotionally immature approach that risks reducing awakening to an achievement or state while bypassing crucial ethical and relational development.

Both approaches often domesticate what could be revolutionary. Both risk turning the dharma into something that reinforces rather than challenges our fundamental confusions. Both can miss the essential point: that genuine practice isn't primarily about becoming a better adjusted participant in consensus reality or achieving special states, but about a fundamental revolution in our relationship with existence.

The path forward isn't about finding a comfortable middle ground between these two approaches. It requires something more radical: a willingness to let the dharma challenge our most cherished assumptions, whether they're progressive political identities or technological fantasies of optimization.

By recognizing these patterns in our own practice and in the broader Buddhist landscape, we can begin to envision a more integrated approach—one that honors the full potential of Buddhism to transform not just individual lives but our collective relationship with reality.

In the next article in this series, I'll explore how we might move from a focus on the cessation of suffering to an understanding of practice as the endless unfolding of aliveness—a shift that goes beyond the limitations of both strains of Western Buddhism while offering a more profound vision of what practice can be.

As someone who has (also) dedicated lots of time to both of these camps (from sitting retreats at IMS to building meditation tech products to jhana practice), I found myself nodding along to a lot of this. The shift to suffering as an irreplaceable feedback loop feels especially important — so so so powerful.

The thing I find myself coming back to after reading this is — how is the comparison of these schools of western Buddhism different than what you might see from someone critiquing, say, two different schools of eastern Buddhism? (Enlightenment buttons aside 🤦♂️)

Each school represents some heavy cultural influence mixed with a pedagogy that emphasizes certain aspects of the dharma differently. Joseph might say (as he did in one dharma) that they all represent different skillful means.

Very curious your take on jhourney & where you see them and similar projects fitting into this model?